The material below is drawn from a book entitled “Blood River” by Telegraph

journalist Tim Butcher. Merging travelogue with history, he recounts a trip

undertaken in late 2004, retracing the route taken by Henry Morton Stanley when

he explored the Congo River in 1876-77. The journey covered nearly 2,500

kilometres, passing through the savannah of Katanga in the south-east, the

jungles of Maniema, equatorial Africa, Kinshasa, the rapids through the Crystal

Mountains and the port city of Boma near the Atlantic coast. Throughout the trip

he gives a detailed account of the history associated with each area.

Butcher’s trip was eventful and highly dangerous. His meticulous preparation

combined with good fortune enabled him to complete the journey, deviating from

the actual route taken by Stanley only twice in the lower reaches of the river.

He travelled overland by motorbike, by “pirogue” (dugout canoe), United Nations

patrol craft (barge/pusher boat), helicopter (for about 600 k) and jeep (the

final leg from Kinshasa to Boma). Two stretches of the river were not navigable

due to series of cataracts (rapids). Stanley had circumvented them by carrying

his collapsible boat overland. He had a huge support team, including native

porters.

Details of Butcher’s trip have not been summarised here. The following is a

summary of his historical information.

CONGO: A BRUTAL HISTORY

Originally inhabited by pygmies, the area now known as the Democratic Republic

of the Congo was later populated by invading neighbouring tribes. Life remained

tribal and varied from relative peace to periods of inter-tribal strife. A

Portuguese explorer was the first white man to discover the mouth of the Congo

River on the west coast of Africa in 1482. It was explored only a short distance

inland. Meanwhile Africa’s east coast was penetrated as far as Lake Tanganyika,

leaving the vast area of central Africa unexplored. But long before the heart of

Africa was conquered and its rich supply of minerals discovered a thriving trade

had developed on the fringes of the region: capturing and exporting slaves.

The history of slavery in the Congo can be traced back centuries. Rival tribes

were relied on to return to their village with a supply of slaves after a

successful campaign. The Portuguese began slave trading in small but steadily

increasing numbers in the early 1500s. A plea was sent to the Portuguese monarch

in 1526 by Congolese leaders to stop slave-trading, claiming “… so great is the

corruption and licentiousness that our country is being utterly depopulated …..”

Little heed was taken and the lucrative trade continued.

For four centuries up to the 1800s other European countries, notably Britain and

Holland, also plied the Atlantic coast capturing slaves. Until the 1860s slavery

had been the only European interest in the Congo but it was about then that

Britain’s Royal Geographical Society decided to enter the “final frontier beyond

the river mouth” with a view to influencing the area in more positive ways. This

led to a series of expeditions, most famously that of

Scottish explorer Dr David Livingstone. Livingstone had first visited

Africa in 1840 and in later years made a number of daring ventures to the

interior south of the Congo. He was a church missionary, teacher and medical

doctor and resolved to spread Christianity as widely as possible in the

continent, improve the health of the natives and campaign against the horrors of

slavery. He was also a prolific writer and published a book and many papers on

his travels, discoveries and on the nature of tropical diseases. As an explorer

he was attracted by stories of a “great river” through central Africa. The story

was perpetrated by the Arabs who had secured a toe-hold in the east of the

country from their slave-trading base in Zanzibar established at the beginning

of the 19th century. The island of Zanzibar became a launching pad

for a number of expeditions from Britain into the eastern and unexplored region

of Africa. In 1866 Livingstone reached Lake Tanganyika and ventured overland

from there to discover the upper reaches of the Congo River. He assumed it to be

part of the Nile river system and did not connect it with the huge river already

discovered on the west coast. His health deteriorated and a letter dated 30 May

1869 was the last received in England. Further letters had been sent but failed

to reach their destination. By 1870 he was declared lost. Search parties were

dispatched but failed to locate him.

HENRY MORTON STANLEY

Stanley was a Welsh-born naturalised American who was abandoned by

his parents and emigrated to the USA as a teenager by working his passage to New

Orleans. He was adopted by a businessman - hence the name Stanley. He fought

from time to time on both sides in the American civil war and then began a

career as a journalist covering later wars between native Americans and pioneers

heading westward. Syndicated to the New

York Herald he developed a reputation for reporting from remote trouble

spots in east Europe and Asia. In January, 1871 he landed in Zanzibar to begin

his most famous undertaking – a search for David Livingstone. Earlier searches

commissioned by the Britain’s Royal Geographical Society had been unsuccessful

and Stanley’s Herald sponsored search

was launched in secret lest the RGS, who regarded Livingstone as “their man”,

should attempt to block it. After 236 days including bouts of sickness and

encounters with hostile tribes, Stanley was directed to the town of Ujiji where

a “sick old white man” was rumoured to reside. They met in the town, on the

eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika, on 27 October, 1871 and spent several months

together. Livingstone refused to return to Europe and died in Africa in May,

1873 aged 60.

Stanley’s interest was aroused, especially with regard to the river Livingstone

had discovered. He made plans to explore and map the river, seeking support from

his employer, the New York Herald and

also put the proposal to the British

Telegraph. Playing one off against the other, he eventually attained the

joint support of both. He prepared for the journey in Zanzibar and set out from

Bagamoyo in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) on 17 November, 1874. He entered the Congo

from Rwanda on 14 September, 1876. He first sighted the river (known as the

Lualaba at that upper point) on 17 October.

His courageous journey (accompanied by a party of 352 native bearers) was

eventful with thirty-two encounters with unfriendly local tribes armed with

poison-tip arrows and wary of slave traders. They communicated with tribes

down-river by way of jungle drums. Despite the opposition, Stanley successfully

reached the town of Boma near the mouth of the river on 12 August, 1877. His

party had carried his collapsible boat (Lady Alice) through thick jungle to

circumvent two long stretches of the river made un-navigable by rapids and

waterfalls. Stanley did his share of the work required to clear paths through

the jungle, not leaving it all to the natives as other white explorers had done

and were to do.

He documented the trip in a book “Through

the Dark Continent” but was unsuccessful in gaining British support for his

plans to return to Africa. When word of his discovery of a navigable river

through the heart of Africa reached the ears of King Leopold II of Belgium he

recognised it as an opportunity. Other European powers had begun colonising the

coastal areas of Africa. Here was a chance for Belgium to stake a claim over the

huge central portion. He commissioned Stanley to journey up the river from the

Atlantic coast and negotiate land deals with the natives. It marked the start of

what became the “Scramble for Africa”. It was also the end of true democracy in

the Congo region. Until then a tribal system operated where villages elected a

chief and paramount chiefs presided over wider areas. Although the chiefs

wielded total control, unpopular chiefs could be replaced by the people. Never

again would the common people exercise this level of power, whether under white

colonial rule or under the rule of black dictators after independence. The elite

classes invariably put self-interest ahead of the interests of the general

population.

EUROPE CARVES UP AFRICA

Other European countries emulated Leopold and forged their way into central

Africa. France, Germany, Portugal, Spain and Britain attended a conference in

Berlin in 1885 to carve up and share out what remained of the continent. Arabs

were conspicuously absent from the conference, despite their presence in central

Africa since the early 19th century. Leopold’s territory was claimed

as a fait accompli and was declared the Congo Free State, owned personally by

Leopold. Totalling three million square kilometres it was the largest piece of

land ever claimed by a single person. The south-eastern province of Katanga

projected as a pan-handle into British-held northern Rhodesia (later Zambia) but

was claimed by Leopold for its rich deposits of cobalt, copper and uranium. The

“Free State” status enabled products to be traded freely in and out of the

country but it reality it was all one-way traffic. Leopold’s officials exploited

the resources throughout the rest of the region, mainly rubber, ivory, timber

and further deposits of copper. European goods also plied their way up the river

but largely for the benefit and use of the white population. The wellbeing of

the natives was neglected. The Belgians possessed modern weaponry and

slaughtered vast numbers when local tribes challenged them. Several million

local people died from warfare, disease and malnutrition.

The rich resources were not the only commodity to be traded by outside

interests. The trading of slave labour also continued. The Belgians exploited

this “income source” on a much grander scale after Stanley’s trip and exported

slaves from slave markets near the mouth of the river. By then an even bigger

slave market had been established on the east coast of Africa on the island of

Zanzibar by Arabs who had been penetrating into the Congo since the early 1800s

and were busy plundering ivory as well as slaves. Prior to the arrival of the

Belgians an “Arab Slave State” developed with whole tribes “Arabised” and

inter-marriage creating a hierarchy: Arab elite, Arab/African mulatto mercantile

middle class, African working class, African slaves. Slaves were traded,

imprisoned, or used to haul pillaged ivory overland and on to Zanzibar.

It’s estimated that about twelve million slaves were exported in the nineteenth

century.

Eventually public opinion among Belgians, both at home and among the colonists,

began turning against the institution of slavery. Strife erupted between the

Belgians and the Arab traders. A peace conference in 1887 was convened by

Stanley himself and Arab leader Tippu-Tip, who had advised Stanley on his trip

down the river in 1876 and helped clear the way for him. But trouble resumed in

1892 when the Arab massacre of two Belgians triggered a reaction so ruthless and

severe, and supported by a fierce (coerced) African tribe, that it has been

compared to the crushing of the Peasants’ Revolt in India by the British. From

that point Belgium re-asserted its dominance in the Congo and slavery diminished

although an Arab presence remained.

By the Edwardian era human rights groups were campaigning against the cruelty

and violence carried out in the Congo Free State in Leopold’s name. The

invention of the inflatable rubber bicycle tyre and the rise of the motor car

increased the demand for rubber. This resulted in even more cruelty as natives

were coerced into increasing their rubber harvest. Chopped off hands was the

standard punishment for workers who did not meet their quota. Attempts by

Leopold to keep this barbaric practice secret were unsuccessful. European

missionaries were among the whistle-blowers and by 1908 international outrage

forced Leopold to cede control of the whole region to the Belgian state whose

government and officials were supposedly more committed to the rights of the

native Congolese. The Congo Free State became Belgian Congo in 1908. A modern

civilisation and infrastructure was established but it was run by whites with

the natives remaining second-class citizens. Three or four major cities arose

but tribal and village life continued as before. The period of colonial rule

from 1908 to 1960 was relatively stable but kept that way by the iron fisted

control of the colonial masters. Deposits of gold, diamonds and cobalt were

discovered during the Belgian colonial era. Mining of these resources continued

after independence with the mining companies foreign-owned until nationalised by

Mobutu in the latter half of his dictatorship.

The colonial era included visits by well-known westerners. Joseph Conrad wrote

“Heart of Darkness” (published in 1899) while captain of Congo River steamboats.

The story immortalised the 1,734 kilometre stretch of the river between the

capital Leopoldville (now Kinshasa, the only modern city remaining in the Congo)

and Stanleyville (now Kisangani). Evelyn Waugh visited Albertville (now Kalemie)

in 1930 and wrote of his experience. Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn

starred in the movie

“African Queen” in 1951, staying at a luxury hotel in Ponthierville (now Ubundu)

and filming in the jungle down river from there.

INDEPENDENCE

As the influence of western educated African leaders increased in the 1930s, the

Atlantic Charter was signed by Roosevelt and Churchill in 1941, proposing

autonomy for the African colonies. The trickle of countries declaring

independence began in 1951 (Libya was the first) and became a torrent in 1960

when sixteen countries shrugged off their colonial shackles. Belgium reluctantly

granted the Democratic Republic of the Congo independence on 30 June, 1960.

British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s famous “Wind of Change” speech on 3

February, 1960 was influential. A 30 year plan had been published in Belgium in

1955 providing for self-government of the Congo.

Immediately after independence and the election of Patrice Lumumba as Prime

Minister the army mutinied and

Moise Tshombe declared the mineral-rich south-eastern province of Katanga

a separate

independent

state. Belgium supported the breakaway but insisted that their mining

interests were protected. Trouble broke out when President Joseph Kasavubu

dismissed PM Lumumba. Lumumba was assassinated in 1961 with suspected Belgian

and US complicity. Joseph Mobutu,

later to lead the country from 1965 to 1997, was a leading figure in the coup.

The United Nations intervened in what became a complex civil war involving

widespread use of mercenary white soldiers. They fought both for and against the

government, for and against the United Nations – some, like Che Guevara, fought

for socialist ideals, many others sought only profit and adventure. The

peace-keepers were also confronted by Belgium-backed rebel Congolese natives.

The UN eventually disarmed Katangese soldiers, whose fight for independence

triggered the civil war. UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold died in a plane

crash in September, 1961 while shuttling between warring factions.

In 1963 Tshombe agreed to end Katanga’s secession and the following year he was

appointed Prime Minister by Kasavubu.

In 1964 there was a violent uprising by a group called the Mulele-Mai (named

after Pierre Mulele, a north-eastern tribal leader) who attacked everything

associated with white rule – not just white people but native run institutions

set up during the colonial era. Whites and natives alike fled when his soldiers

approached. The plight of the Congolese attracted world-wide attention during

this period, reminiscent of the Edwardian outrage over Leopold’s excesses at the

beginning of the century.

In 1965 Mobutu displaced Tshombe and Kasavubu in another coup. The United States

backed his rise to power as he was seen as a safeguard against Soviet influence

taking root in central Africa. This brought the war to an end and a degree of

stability was achieved. Much of the Belgian infrastructure was retained under

Mobutu.

THE MOBUTU ERA AND CONGO'S MODERN HISTORY

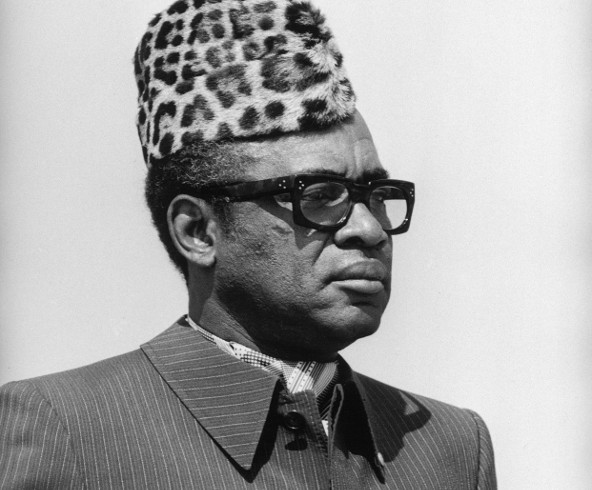

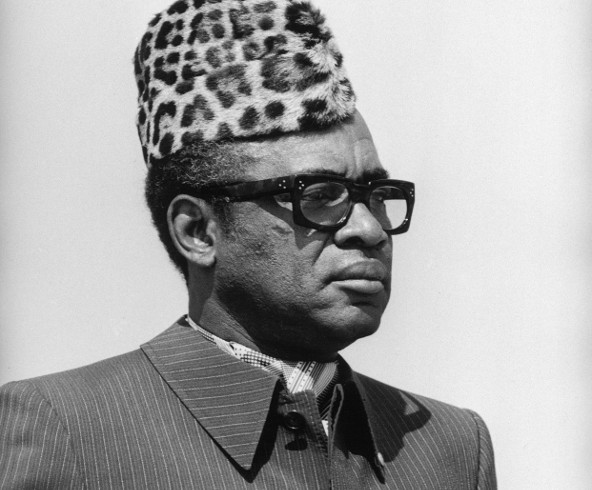

Mobutu Sese Seko

By 1971 Mobutu, now known as Mobutu Sese Seko, had become corrupted with power

and engaged in a programme to stamp his personality on the country. He renamed

it Zaire and nationalised many foreign–owned firms. European investors

abandoned the country. Intertribal conflict and incursions by tribes in

neighbouring countries followed later in the 1970s and economic problems arose

in the 1980s. Mobutu’s rule began to crumble in the early 1990s. The Congo

became caught up in the aftermath of the horrific genocide in Rwanda in 1994

when the minority Tutsis (who had been favoured by the Belgians during the

colonial era, continued to dominate the Government and had been hated by the

majority Hutus ever since) were massacred in huge numbers by the Hutus. Over

800,000 died in the month of July alone. The Tutsis regained control of Rwanda,

with support from Uganda, and many Hutus, fearing revenge attacks, crossed the

border into the Congo. Incursions by Tutsis into the Congo to attack Hutus added

to the ongoing internal tribal strife. Villagers followed a standard response

when hostile tribes entered their territory. They fled into the bush, returning

to rebuild their lives from what was left of their houses, crops and livestock –

usually very little.

The Mobutu era ended when he was toppled by Laurent Kabila in 1997. Mobutu

claimed the support of the Hutus, while Kabila’s successful bid for the

leadership was backed by Rwandan Tutsis. After the regime change the country

reverted from Zaire back to

the

Democratic Republic of the Congo. Mobutu died in

exile in Morocco later in 1997. Things did not improve and in 1998 serious

inter-tribal strife escalated. Soldiers and civilians from Rwanda and Uganda who

had entered the country in support of Kabila remained to exploit the mineral

resources in the east of the Congo and eventually Kabila turned against them.

The four year war that followed drew in troops from Namibia, Angola, Chad and

Zimbabwe (in support of Kabila) and from Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi (against

him). An accord was signed in 1999 by six countries and the United Nations moved

in to monitor the “peace”. Despite this, war continued to rage with Government

and foreign rebels pitted against rebels from Uganda and Rwanda. 2.5 million

people died as a direct or indirect result of the war before three more peace

treaties were signed in 2002. River passage was almost impossible during the

1998-2002 period of the war, especially the last two years. In January, 2001

Kabila was shot by a bodyguard and succeeded by his son Joseph.

Clashes continued, notably in 2004 in the town of Bukavu (on the border with

Rwanda) when pro-Rwandan/anti-Congo Tutsis broke the peace agreement and

massacred scores of people. Congolese retaliation almost led to a resumption of

the war. Thereafter all pro-Rwandan tribes were viewed with suspicion, even

those long based in the Congo. In 2006 the first genuine election since 1960 was

held, won after a run-off by the incumbent Joseph Kabila.

2009-2011 saw a number of arrests for crimes of genocide and mass rape committed

during the 1998-2002 civil war. Strife between opposing factions continue to the

present day.

The above historical summary from Tim Butcher’s book "Blood River" was penned by John Kiley in June, 2011.