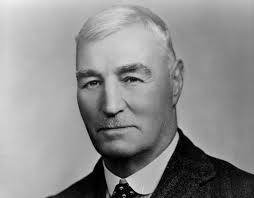

1869 - 1947

George Forbes is probably New Zealand’s least

remembered and least respected prime minister and one who nobody believed could

ever rise to occupy the top office. His political career involved a series of

coincidences and climaxed the way it did largely due to his party diminishing to

the point where he was practically the only man left standing. He was absorbed

into a new party led by Joseph Ward who unexpectedly won the 1928 election.

Forbes became deputy prime minister and, on Ward’s resignation due to

ill-health, prime minister. It was an astonishing succession of events and

Forbes was destined to spend most of his ministry shackled in a coalition

arrangement with the Reform party which had previously been a bitter rival.

Forbes lacked leadership qualities, charisma,

media skills and ambition. But as a person he was amiable with a sense of humour

and natural affinity with his constituency which he represented for 35 years. He

believed in the values of the common man and was opposed to any policies aiding

the wealthy.

Forbes was a good debater and could grasp

technical details but lacked intellectual depth and was seen as a relic of the

past - the last of the liberals in the Ballance/Seddon/Ward tradition who

believed that government should work in the interests of all sectors of the

community and involve itself in a wide range of activities, notably

infrastructure. This tradition had all but died out when Forbes entered

parliament in 1908. New parties were arising to cater for specific interest

groups and the now universal left/right divide was emerging.

George Forbes showed an early interest in

public affairs and politics. Born in Lyttelton he spent only two years at

Christchurch Boys’ High School before obtaining work in a merchandising company

and later with the family hardware firm. He read books on British political

history and joined a debating society. He heard George Grey speak and admired

and befriended George Laurenson who later became MP for Lyttelton. Forbes

obtained leasehold property in the Cheviot area in 1893 and became a foundation

member of the Cheviot county council. One of his political failings during his

later parliamentary career was his lack of empathy with the urban population,

knowing only the rural life-style of a leaseholder.

By 1902 George Laurenson was in parliament and

Forbes was keen to join him. Richard Seddon saw potential in him but thought he

was not yet ready and refused to endorse him. He stood anyway, competing against

the official Liberal candidate. Needless to say he lost but two years later

Seddon appointed him to a Royal Commission inquiring into land policy, an

extremely divisive topic at the time. He handled the job well. The commission

members travelled over 7,000 miles and held 135 meetings to hear submissions.

Forbes’ relentless support for the leasehold system was evidenced by a

dissenting minority report which a group of commissioners led by Forbes

submitted, proposing that the freeholding of leases should be allowed in only

very specific circumstances.

Forbes’ travels as a commissioner made him a

well-known figure nationwide, especially in the rural community, and he won his

way into parliament in 1908 as a Liberal member for Hurunui under Joseph Ward

(Seddon had died in 1906). His high profile and considerable degree of local

popularity kept him in the Hurunui seat until his retirement in 1943.

In parliament he remained a staunch supporter

of the leasehold system and defended it even after admitting in the house that

he could make a tidy profit if he converted his own holding to freehold. “We are

not here to try and put money in our own pockets,” he was quoted as saying. “We

are here to represent the people.” His honesty and care for others were

hallmarks of his career.

As a back bench MP Forbes continued to uphold

the outdated policies of the 1890s, attempting to straddle what was by 1908 a

clear left/right divide with Massey’s Reform party looking after private

enterprise and land freeholders while emerging socialist parties (eventually to

coalesce as Labour) saw themselves as the saviours of the working class.

After the resignation of Joseph Ward in 1912

and with the party numbers beginning to wither one would expect a man destined

to lead his party and eventually lead the country as prime minister would have

begun to show his head above the rest by now. Far from it. Thomas Mackenzie took

over as prime minister in 1912 and rejuvenated his cabinet but Forbes wasn’t

included and the Liberals were defeated that same year anyway. When Ward

regained the leadership in 1913 a warm relationship was reignited with his

earlier disciple but still Forbes was not elevated to the opposition front

bench. There was talk in the press that he might be included in the national

wartime Reform/Liberal ministry formed by Massey in 1915 but again he was passed

over nor did he fill a vacancy which occurred in 1917. By 1919 the wartime

ministry was disbanded and the Liberals were back in opposition. In the election

that year Ward himself lost his seat leaving the party in need of a new leader.

Still no Forbes. One of his fellow MPs from the 1908 intake, William MacDonald,

was chosen and when MacDonald died after only ten months the leadership went to

Hutt MP Thomas Wilford – considered a marginally less boring speaker than

Forbes. It was only when Wilford resigned to travel to England for medical

treatment in 1925 and the caucus was reduced to only 19 members that the party

finally turned to Forbes as their

replacement leader. The Liberals were in their death throes. Rebranded as

National (not the present day National) they were heavily defeated in the 1925

election with only twelve members surviving including the re-elected Ward who

continued to call himself a Liberal. A by-election win by Labour in 1926

increased that party’s strength to 13 and made them the main opposition. Forbes’

brief term as opposition leader had come to an end.

He had now been in parliament for seventeen

years. But he had not been idle. He was tirelessly promoting land reform and by

1912 had been elevated to chief party whip for the Liberals, remaining in that

position for 11 years. This role suited him. He mixed well with caucus members

and was a good listener.

Reverting back to the months preceding the

1925 election, Forbes had seen the party he led withering away and another rival

party, Labour (with seventeen seats), rising rapidly to threaten its survival.

This prompted Forbes to engage with the new Reform leader Gordon Coates (Massey

had died earlier that year) with a view to fusing their parties, rivals up to

this point, to counter the rise of Labour and contest the election as a single

entity. Coates was not interested and led his party to a spectacular win on its

own. Ironically, had Forbes succeeded in his attempt to combine the parties he

would never have become prime minister as Coates would undoubtedly have remained

leader of the combined party.

Similarly, he would never have become prime

minister had it not been for the actions of a wily entrepreneur named AE Davy.

Davy had masterminded Coates’ successful 1925 campaign but abandoned Reform in

1927 to launch a new party he called United, made up of a few remaining

Liberal/National members and supporters of the 1928 committee of urban

businessmen. Forbes became its titular leader despite his initial reluctance as

he saw it as a party favouring the wealthy. His leadership was temporary as Davy

was seeking a more charismatic leader for the upcoming 1928 election campaign.

He persuaded the ailing 72 year old Joseph Ward to assume the mantle, with

Forbes appointed as one of two deputies.

In dramatic, almost farcical circumstances in

which Ward mistakenly promised a seventy million pound loan from London, the

United party won the election. This elevated Forbes to deputy prime minister and

finally, after 20 years in parliament, into cabinet. He performed well as

minister of lands, agriculture and justice, with land, predictably, an area of

particular interest to him.

Ill-health forced Ward to resign in May, 1930,

but deputy Forbes was even now not a certainty to succeed him. Nonetheless he

won a four way ballot and his slow-burning low profile parliamentary career

suddenly burst into the headlines. After only eighteen months in cabinet he was

prime minister. The press and the entire nation wondered how this could possibly

have happened.

Forbes’ United party was still a minority

government needing support from, ironically, Labour, and a few independents.

Their caucus totalled 26.

The United ministry was unspectacular. Forbes

himself appeared to lose all interest in what went on around him after speaking

in the house. He also developed a reputation for stubbornness once he’d made up

his mind on an issue. The government was on the back foot from the start. The

Great Depression had begun to bite and there was a huge balance of payments

deficit. Popular support for Labour was mounting and Reform’s Gordon Coates was

finally persuaded by his colleagues that coalition with United would be in his

party’s best interests leading up to the next election. An agreement was sealed

in September, 1931. It added strength and experience to the government enabling

Forbes to survive the 1931 election as prime minister but the threat from Labour

kept growing. And the depression kept deepening. Reform ministers carried the

bulk of the workload but Forbes nursed mortgage relief legislation through the

house and devalued the currency to assist farmers. Nevertheless the country

remained in chaos. Unemployment and low workers’ wages led to riots in 1932,

mainly in Auckland’s Queen Street.

The Keynesian method of big government

spending to stimulate the economy in bad times lay well in the future, leaving

the government seemingly no other option but to cut costs. Attempts were made

through local bodies to provide emergency work but this eventually ran out and

the government was forced to begin paying the dole in 1934. It should have been

election year in keeping with the traditional three year cycle but the

government postponed it in the hope the country could claw its way out of

trouble. Despite small improvements through devaluation and more favourable

economic conditions overseas, the coalition was soundly defeated by Labour in

1935. Forbes had been prime minister for five and a half years – four and a half

yoked with Gordon Coates in the United/Reform coalition.

Forbes resigned as United’s leader in 1936 and

the two opposition coalition partners officially combined to form the present

day National party. Neither Forbes nor Coates was considered for the leadership

of the new party – both were tainted by the depression years. Adam Hamilton was

chosen, soon to be replaced by the much longer-serving Sidney Holland. Forbes

lapsed into an insignificant opposition MP and he left parliament in 1943.

He died at his Cheviot farm in 1947 aged 78.

Forbes’ political career was far from illustrious. But he was seen as a good man who lacked the leadership qualities required to head a government, and his term as prime minister took place at a very low point for his party, the county and the world.

Goto next Prime Minister: Michael Joseph Savage