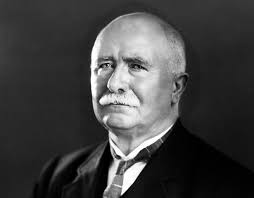

1856 - 1925

William Massey served twelve years and ten

months as prime minister, just three months less than New Zealand’s

longest-serving leader, Richard Seddon.

From 1903 Massey led the first party to be set

up in opposition to the Liberals. It was the forerunner of the Reform party and

differed markedly from the Liberals over land tenure (Massey’s party favoured

freehold land for farmers) and industrial relations, in which Massey showed a

firm hand dealing with the 1912 Waihi miners strike and the much more widespread

and brutal waterfront and general strike in 1913. While the Reform party was

without doubt to the right of the Liberals, their hold on power was so tenuous

that Massey felt compelled to follow the interventionist policies of the

Liberals in most mainstream issues. Indeed his own liberal leanings prompted him

to make small incremental increases in welfare payments and education support.

His government also subsidised key industries.

Nonetheless the party established its own

identity and declared itself a firm supporter of private ownership, urban

business and farming. Unlike the Liberals whose later attempts to be all things

to all people led to their demise, Reform entrenched its position in opposition

to the emerging Labour movement with its support base of trade unions and the

working-class.

There were inevitable personal comparisons

drawn between Massey and Seddon. Both had a powerful presence, a booming voice,

limitless energy and through sheer length of service, both became a trusted

institution generating wide-spread personal popularity. But differences were

also striking. Fast-speaking Massey was the more agile debater although a little

clumsy in his use of language. Seddon appointed politicians of a lesser calibre

than himself to his cabinet to ensure his supremacy; Massey’s was stacked with

university graduates whose input he valued and who served him well during his

long absences overseas, particularly during the war years. A third difference

was that Massey established an independent public service commissioner to

appoint public servants thus avoiding political cronyism and other forms of

discrimination. Seddon believed ministers should choose their own public

servants.

William Massey was born in Northern Ireland

with half-Scottish heritage. His parents emigrated to New Zealand when he was

just six years old, leaving him back at home in the care of his grandmother.

Eight years later, in 1870, young William followed his parents to New Zealand

aboard the square-rigged clipper City of

Auckland, learning a range of sailor’s skills during the 84 day voyage.

Travelling alone half-way round the world endowed the brave 14 year old with a

large measure of self-reliance that would serve him well in later life.

Massey’s early employment in New Zealand was

farm work – initially on his parents’ property in Auckland and later on

Longbeach Station near Ashburton. He worked extremely hard and was able to

purchase a 100 acre farm in Mangere, equipped with a threshing machine which he

contracted out.

By the early 1890s Massey, now well into his

thirties, had become a local identity involved in numerous activities and

organisations. A staunch Presbyterian, he was a senior warden of the Manukau

Freemasons' lodge. He was on the Mangere roads board, chairman of the Mangere

school committee and was active in the local debating society. Most importantly

he was chairman of the Mangere farmers' club, which in 1890 revived the Auckland

Agricultural and Pastoral Association of which Massey became president from 1890

to 1893. As such he was the de facto spokesman for farmers in the entire

Auckland province. This last position led to Massey being chosen as vice

president of the National Association of New Zealand, a political body formed in

Auckland in September 1891 to organise urban and rural conservatives against the

new, more radical Liberal government led by John Ballance. This organisation

would eventually become the Reform party.

Massey’s first attempt to enter parliament was

in his home electorate of Franklin in 1893. He was unsuccessful but in April,

1894 a vacancy occurred in Waitemata, a far-flung electorate in the west and

north of Auckland. He stood again and this time was elected. His parliamentary

career had begun but could well have ended after just one term. The small,

dispirited, loosely organised collection of conservative independents Massey

joined in the parliamentary opposition were no match for the dominant Liberal

government of Richard Seddon. Massey admired and liked Seddon but the opposition

leader, William Russell, was supported by a mere fifteen of the total of

seventy-four parliamentarians. Massey seriously considered not standing again

but he became respected for his tenacity and clarity in debates and in time

revealed his astuteness as a tactician and organiser. By 1896 he was the

opposition whip.

Having decided to stay in politics he had the

chance to again contest his home electorate of Franklin at the next general

election. This time he won and would retain the seat for the remainder of his

life. The Massey era had begun.

As a group the opposition (now almost doubled

in number to twenty-eight) adopted a more clear-cut conservative position on

land tenure, labour legislation and infrastructure. Massey himself became the

prime advocate for freehold land. He emphasised the importance of individual

responsibility, initiative, incentives and rewards. He strongly supported the

construction of the main trunk railway between Auckland and Wellington.

By the 1899 election Seddon was at his peak

and the opposition was again cut back to just fifteen. Between 1899 and 1902 the

government’s hold on power was further consolidated by the South African war,

economic prosperity and industrial harmony. The opposition's position

deteriorated. During most of that time Massey, as whip, served as

de facto leader.

The 1902 election saw little change in the

relative strengths of the government and opposition. It was clear that the time

had come to officially seek a robust, effective and credible opposition leader

to devise and manage tactics in the house and to appeal for support in the

electorate at large. Massey was just the man and he was unanimously elected on 9

September, 1903. But even Massey’s powerful presence made little impact on

Seddon’s rock-solid hold on government and the 1905 election was yet another

decisive victory for the Liberals. Then came a game-changer for NZ politics and

for Massey: Seddon’s sudden death on 10 June 1906. After allowing a respectful

grieving period Massey awaited his chance to make a decisive move and it came

when Liberal finance minister Robert McNab announced a tightening of the

leasehold land laws. As land tenure was a divisive issue Massey pounced on it,

declaring to the country that his party was the one to vote for if you supported

freehold land ownership.

Despite Massey’s energetic campaigning, the

Liberals, now led by Joseph Ward, managed one more clear election victory in

1908 but became aware of the threat posed by a credible opposition whose

representation had now reached 26 seats. Massey’s party was picking up support

from the wealthier city suburbs to augment his rural voter base. In 1909 he

announced his party would now be known as Reform.

Reform’s star rose in 1911. The election

result was indecisive with the emerging Labour movement now part of the

political scene. Two confidence votes were held – the Liberals won the first but

several key independents changed their votes in the second resulting in Massey

being invited to form a government on 10 July, 1912. This brought the Liberal

government’s 21 year term in power to an end. By now Massey was a nationally

known figure, with a dominating presence to rival Seddon’s.

Throughout his eighteen year term in

opposition Massey had never wavered from his key policy platforms nor did he on

becoming prime minister. Needless to say he introduced legislation enabling

freehold land tenure for crown tenants. Later he would set up stricter methods

for investigating and settling labour disputes. He

introduced a parliamentary services commissioner. He

was supported in government by able and well-educated ministers, notably James

Allen, Francis Bell and William Herries.

From day one Massey found himself dealing with

industrial strife. A miners’ strike in Waihi had been declared two months before

the Reform government came to power. To sketch out the background, the

industrial legislation of the day had been put in place early in the Seddon

ministry. The Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act of 1894 set up a

binding arbitration process and the country was mainly strike-free from then

until 1908. Miners in the West Coast town of Blackball then went on strike over

meal breaks, pay and conditions in defiance of the arbitration system, claiming

it had failed them and wages had not kept pace with inflation. After Blackball

had shown the way miners unions combined to form the NZ Federation of Miners and

many member unions followed Blackball and de-registered from the Arbitration

Act, legally enabling direct negotiation with employers and the right to strike.

In 1910 the Federation opened its door to non-mining unions and was re-named the

NZ Federation of Labour, further enlarged in 1913 to become the United

Federation of Labour. On the other side of the table the NZ Employers Federation

and the Farmers Union viewed this development with alarm, fearing rampant

socialism.

The matter at issue in Waihi was the

juxtaposition of the Federation-affiliated Waihi Trade Union of Workers and the

arbitrationist Stationary Engine Drivers Union. Put simply, the trade-union

workers refused to work alongside the engine drivers and withdrew their labour.

Faced with industrial trouble at the country’s biggest gold mine Massey had no

hesitation in applying the full force of the state in bringing the miners to

heel and in this he had the enthusiastic support of the country’s newly

appointed Commissioner of Police, John Cullen. The heavy police intervention

crushed the union, strikers’ families were ordered out of town and there was

even one fatality. It was a decisive victory for Massey and the unions now knew

exactly where they stood under their new prime minister – on the back foot.

But that didn’t stop further action in another

location the following year. In October, 1913 sixteen coalminers in the Waikato

town of Huntly were dismissed on account of their connection with the “Red

Feds”, a derogatory moniker given to the Federation of Labour by their

opponents. Those dismissed included three union officials. A lengthy strike

lasting from 19 October to mid-January resulted. It ended when a new union

supporting the arbitration system forced its way to replace the striking union.

Police action in Huntly was more conciliatory than in Waihi.

But it was far from conciliatory during

another dispute which coincided almost exactly with the action in Huntly and

turned out to be New Zealand’s most violent and divisive strike action in its

history. It began simply enough, with the Wellington Shipwrights Union striking

over travel time, pay and conditions and the Union Steam Ship Company unable to

reach an agreement with them. Had the union signed up to the arbitration system

the matter could well have been resolved quickly. But the shipwrights were

affiliated to the Wellington Watersiders Union, one of the largest and most

militant in the Federation of Labour. The matter would not be resolved quickly.

The strike had begun on 18 October and four days later the watersiders held a

stop-work meeting to consider their options over the shipwrights’ action. They

returned to work to discover other workers had been hired to fill their jobs.

The employers promised to reinstate the original workers if they agreed to

register under the arbitration act (or alternatively pay a bond guaranteeing not

to strike). Needless to say, they refused and the strike continued. It spread

rapidly. Watersiders and coalminers throughout the country joined in and other

industries struck in sympathy including seamen, drivers and labourers. Workers

on strike would eventually exceed 14,000. The employers joined forces in

powerful Employer Defence Committees in Wellington and Auckland. A huge

stand-off loomed.

The first major instance of violence was on 24

October when a swarm of strike supporters invaded the Wellington wharves and

forced the strike-breakers to stop working. Massey could see immediately that

the police would need support to maintain order. The obvious choice was the

military but army head Colonel Edward Heard was reluctant to become involved. He

suggested augmenting the police numbers by recruiting territorial-style

reserves. Massey welcomed the idea and a nationwide call for volunteers was

issued. The response was immediate, especially from the rural sector which was

more severely affected by the strike. Hordes of farm workers descended on the

main centres and were issued with wooden batons and in some cases revolvers.

Many rode in on horseback and carried horse-whips. They were a formidable strike

force and in Wellington alone numbered over a thousand. Their official title was

“Special Constables”, shortened to “Specials” and dubbed less charitably

“Massey’s Cossacks”, after the famed Russian military horsemen. In addition

there were volunteer “Foot Specials”, recruited among city workers, students and

sportsmen.

In Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin the two

sides rarely clashed but not so in Wellington. Within twenty-four hours of the

Specials’ arrival on 29 October there were two violent confrontations, one

involving revolver shots. There were injuries but no fatalities. Army machine

guns were deployed and two navy vessels were docked on the Wellington wharves,

also with machine guns at the ready.

The Wellington Specials were accommodated,

fed, supplied and trained by the army and camped in Buckle Street. Local

residents were aghast and rioted in the street in early November. Specials

mounted on horseback charged the crowd. Again shots were fired causing injury.

An even bigger confrontation occurred on 5 November when the Specials were

marching to the wharves to protect the loading of racehorses onto a ship. In

Featherston Street a battle raged between the marchers and the strike supporters

as well as many bystanders who joined in, with the Specials wielding their

batons and the crowd throwing stones, fence posts and anything they could lay

their hands on. Specials on horseback again made a succession of mounted charges

against which the milling riotous crowd was helpless. In due course enough “free

labour” was recruited to get the wharves working again. From there the strike

lost its momentum and ended in mid-January.

The key to resolving the crisis, as with the

Waihi action, was setting up replacement unions loyal to the arbitration system.

It’s worth noting that among the fiery

speakers urging the strikers on were men who would later turn to politics in the

belief they could serve workers’ interests more effectively in that role. Among

them were names such as Semple, Webb, Parry, Sullivan - all of whom would become

government ministers, plus future prime ministers Michael Joseph Savage and

Peter Fraser.

The final chapter in this sorry industrial

saga that faced William Massey in the very early days of his ministry was the

passage of the Labour Disputes Investigation Act, 1913 which brought in new

rules to make striking more difficult and it would be 1951 before any industrial

action on this scale occurred again. Regardless of the side they supported

during the strike, the general public admired, in some cases grudgingly,

Massey’s unwavering confidence, assertiveness and consistency throughout an

event which disrupted the entire country at huge cost.

This was only the beginning of William

Massey’s term which turned out to be precarious and littered with difficulties

throughout. After the strikes a world war loomed to which Massey the imperialist

had no hesitation in committing NZ troops. Then came the 1914 general election.

With the country divided over the strikes and (less so) over the war, the result

was indecisive. With a wafer-thin majority, Massey was forced to invite the

Liberals to join a national wartime coalition and appoint Joseph Ward, a man he

disliked, as minister of finance.

Between 1914 and 1919 both Massey and Ward

were overseas for long periods, visiting troops and attending imperial

conferences. The war years were the highlight of Massey’s political career.

Maintaining troops, reinforcements, supplies and finance as well holding the

reins domestically presented a huge challenge and he rose to it admirably.

Furthermore the respect he commanded internationally was recognised by his

appointment to the imperial war cabinet when it was set up in 1915. On the war’s

conclusion in 1918 he signed the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of NZ.

But the war had devastated the country. New

Zealand soldiers had died in huge numbers on the battlefields of Passchendaele,

the Somme and Gallipoli. The final death toll was around 18,000. Nearly all the

victims were buried overseas and hundreds of war memorials were erected in towns

throughout the country in their memory. Yet another tragedy followed when a

severe influenza epidemic swept the country in 1918 during the last months of

the war, causing a further 9,000 deaths. New Zealand was grieving.

Then came the 1919 election. Massey campaigned

against the Liberals and Labour on a policy of patriotism, law and order,

industrial harmony and the protection of private property. He promised to look

after returned servicemen, expand exports, improve urban housing and spend more

on education and public works, especially railways. The party was now riding a

post-war economic boom and in the election was able to secure what turned out to

be Massey’s first and only clear-cut win. It looked comfortable on paper (45

seats in the house of 80) but it came from only 36% of the popular vote.

Nonetheless Reform was clearly the dominant party – the Liberals won nineteen

seats, Labour eight and independents the remaining eight.

Throughout Massey’s ministry the Liberal party

was steadily disintegrating but with the emergence of the Labour party as the

main opposition the progressive policies that had been the mark of the Liberals

did not die with them. They were partly adopted by Massey’s Reform party and

retained by, first the United party and eventually by the National party.

New Zealand was hit by a sharp depression in

late 1921. Britain’s wartime commandeering of NZ exports came to an end and

there was a worldwide glut of primary products causing prices to tumble.

Returned soldiers who had been assisted into farm ownership were badly hit. Many

of the farms were on marginal land in inaccessible areas and with the high cost

of development and poor returns many simply walked away. In a forerunner of what

was to come ten years later, unemployment soared. Massey responded by reining in

government spending and cutting public service wages. More industrial strife

followed. The seaman’s union called a strike from November, 1922 to January,

1923 and in subsequent years railway workers, miners and freezing workers all

took industrial action. Massey had shown in 1912-13 he was not to be trifled

with. He stood his ground and in each instance the union involved eventually

backed down.

Not surprisingly industrial relations were a

major election issue in 1922 but so too was liquor licensing. A referendum on

the licensing laws had been held with every general election since 1911 and

would continue to 1987. There was strong campaigning on both sides and support

for prohibition came close to a majority in both 1922 and 1925, subsiding after

that. The result of the 1922 general election itself was so close it left Massey

relying on four independent members to keep his majority. Although Reform

increased its popular vote to 39% its seats fell to 37. The Liberals won 22 and

Labour 17.

Massey’s Reform party held on and the country

recovered from the depression. The early 1920s witnessed remarkable

technological and industrial progress. Radio broadcasting began in 1922, cinema

attendance surged and by 1922 rail journeys reached 28 million per year. Several

major hydro-electricity projects were launched, driven by public works minister

and deputy PM Gordon Coates.

But the Massey era was about to come to an

abrupt end. William Massey was forced by illness to relinquish some of his

workload in 1924 and he underwent cancer surgery in early 1925. He fought a

losing battle and died on 10 May, 1925 while still in office. Once again, the

country grieved.

Massey's thirty-one year parliamentary career

was marked by more crises and difficulties than that of any other New Zealand

politician. He inherited a small, unpopular, fragmented opposition that had to

compete against the charismatic appeal of Richard Seddon. His governments from

1912 to 1925 grappled with economic recessions, strikes, public disorder,

growing divisions within society, a world war and the worst ever influenza

epidemic. A three-party splitting of the vote resulted in Massey only once, in

1919, winning a clear victory. Holding the caucus together and managing the

government for nearly thirteen years was a monumental achievement. Although he

never attained the “father figure” status accorded to Seddon and Savage history

has assessed him as one of New Zealand’s most significant politicians whose

greatest achievement was leading the country through the traumatic ordeal of the

first world war.

Massey university and a major west Auckland

suburb carry his name and a very large and impressive white marble memorial

above his grave on Mount Halswell overlooking Wellington harbour was unveiled in

1930.